Puerto Rico 1980-95: Transitioning from Dalmau's to Piculín's generation

The first fifteen years were a honeymoon. The Puerto Rican national team, who initiated the continental championship by winning at home, coincidentally had at the time two of their best generations.

The first fifteen years were a honeymoon. The Puerto Rican national team, who initiated the continental championship by winning at home, coincidentally had at the time two of their best generations at an international level. Except for the United States, who participated in just three of the first nine editions, Puerto Rico was the most dominant team in the Americas from 1980 to 1995, with a 38-14 record, three gold medals, and two silver. At the same time, a transition between two idols was underway, from Dalmau to Piculín, without missing a step along the way.

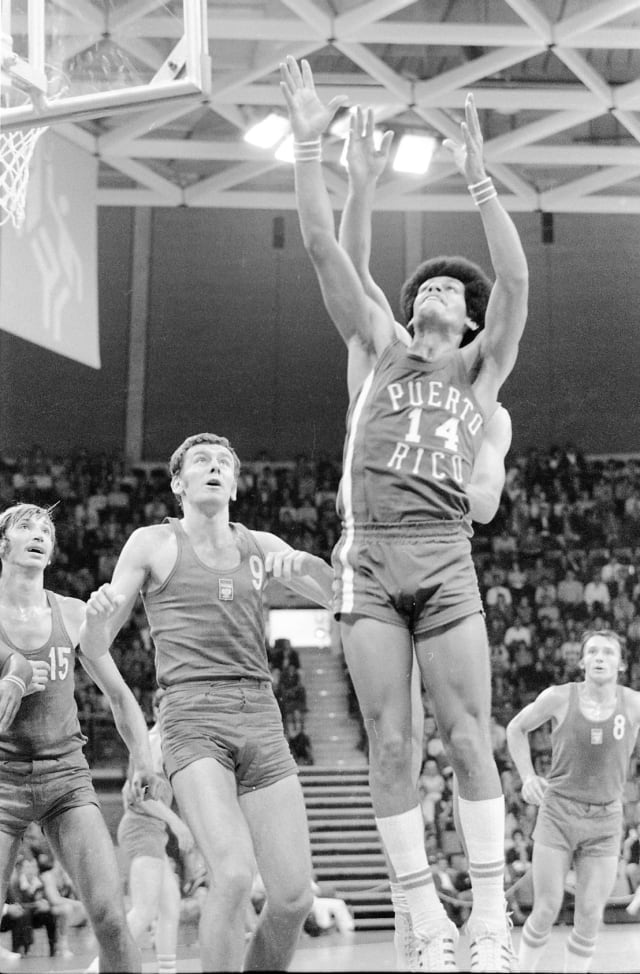

Raymond Dalmau

Raymond Dalmau

The '80s team was balanced and characterized by an offense of several protagonists that each night could be very well led by veterans like Rubén Rodríguez or Raymond Dalmau, or by the explosive duo of young players like Georgie Torres and "Quijote" Morales. Puerto Rico didn't have a single player within the best 12 shooters in the tournament, but it did score 134 points against Mexico (the highest single-game score of the competition).

Mario "Quijote" Morales

Mario "Quijote" Morales

In the first game, Rodríguez scored 17 to win a tight match against Argentina, followed by 21 and 24 by "Quijote" against Uruguay and Mexico. Then it was 18 and 14 by Dalmau against Mexico and Brazil, and the 22 by Georgie to steal away the Canadians' undefeated status. Some players were averaging nearly 10 points per game, including Neftalí Rivera, Angelo Cruz, Néstor Cora, José Quiñonez, and "Cachorro" Santiago. It was an improved version of the team that had rocked the island with their participation in the 1979 Pan American Games. It was that team, but now with Rivera (who was suspended the previous year) coming back in great shape.

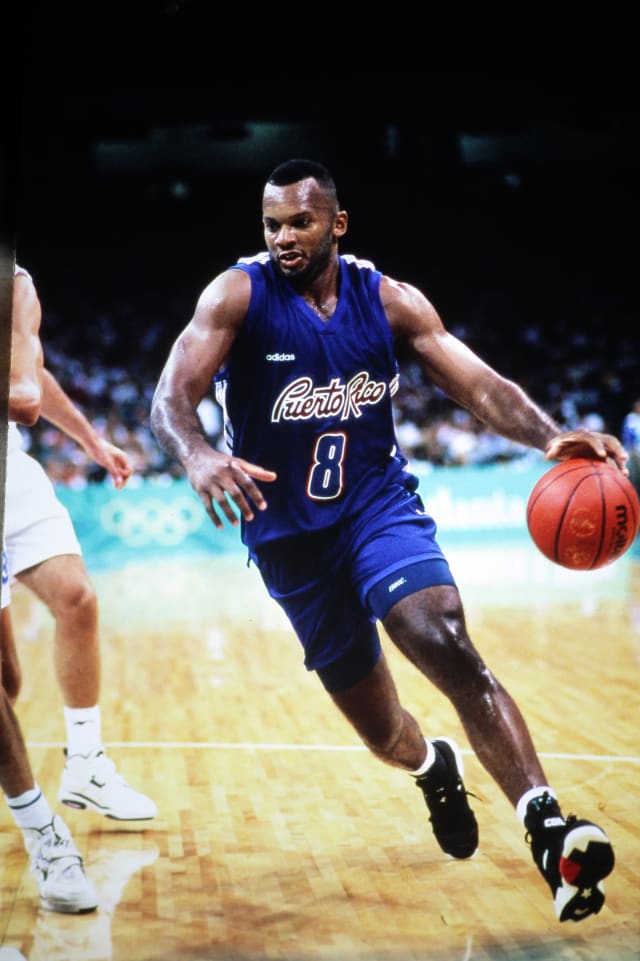

Jerome Mincy

Jerome Mincy

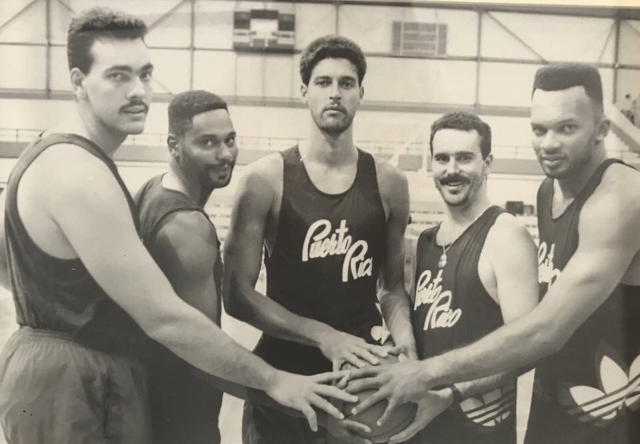

‘84 was the year of the transition. Dalmau, Rodríguez, and Rivera were no longer in the squad. Up-and-coming players Jerome Mincy and José “Piculín” Ortiz were debuting, and Quijote Morales proved to be in his best moment, averaging 16.6 points per game. The team met the demands of, well, a transition team, and fell short against Mexico, Canada, Uruguay, and Panama. But the seed was planted. Ortiz and Mincy would become the leaders of a national team that six years later would be fourth at the world level.

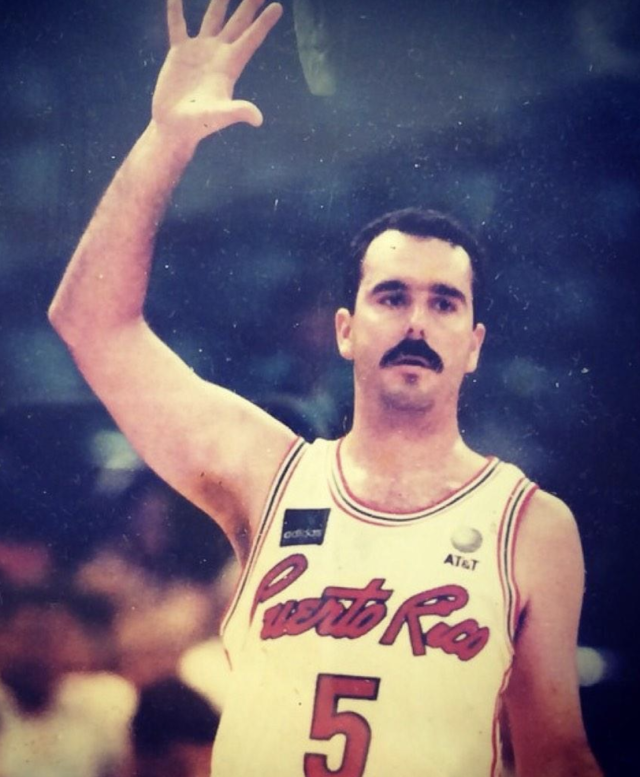

Federico “Fico” López

Federico “Fico” López

In 1988 came Federico “Fico” López, Raymond Gause, and the young Ramón Rivas and Ramón Ramos to a Puerto Rican team that went undefeated to the final and lost 101-92 against a Brazilian team that featured Oscar Schmidt and Marcel de Souza. By that time, Ortiz led the team in scores, with 15.4 points per game. However, the depth of the Puerto Rican squad was so that they won the 1989 edition without Ortiz.

The 89 success was thanks to the Guase-Mincy-Morales-López quartet, all of whom averaged in the double figures, and had great performances in the semifinals against Venezuela, and in the final against the United States. Quijote scored 21 and 20 points in both games. Due to Ortiz's absence, Ramos took unprecedented importance. He was coming in from being an NCAA star in the final with Seton Hall, and would later be signed by the Portland Trailblazers in the 1989 season. Ramos averaged 9.8 points per game and was included among the prospects to look out for in international basketball. Unfortunately, on December 16 of the same year, he lost control of a vehicle he was driving and suffered an accident that ended his basketball career.

The iconic 1992 Portland championship where the Dream Team debuted saw a Puerto Rican team that began and ended losing against Brazil – two defeats that left them away from the podium after having to face the USA in semis because of the initial loss. The bronze medal went to a Brazilian team that won with 27 points by Schmidt, despite outstanding performances by Ortiz and Mincy, with 20 and 25 points, respectively.

In 1993 they went back to the podium with a great tournament by James Carter, who averaged 15.3 points per game. Players Eddie Casiano and Dean Borges debuted in what was the last participation of Morales and López. Ortiz led the team again, with 16.7 points per game, including 18 points in the final they lost against a group of unknown USA players, 109-95.

James Carter

James Carter

‘95 was one for the history books. As Puerto Rican journalist Marcos Mejías said in the roundtable published on Sunday: “Three days before the tournament, Puerto Rico still didn't know what team it was taking to the tournament that granted three spots to Atlanta 1996. Piculín Ortiz, Jerome Mincy, and Ramón Rivas led a second group that many said lacked any chances (because the rest of the best local players were suspended). They ended up winning the tournament 9-1, taking the gold medal and avenged their only defeat (35 points) against Argentina in what was a classic final.”

José “Piculín” Ortiz

José “Piculín” Ortiz

The pre-championship disorganization was overcome by having FIBA Hall of Famer José “Piculín” Ortiz, as well as legendary player Jerome Mincy, in their best moment. Georgie Torres’ comeback was also remarkable, averaging 14.7 points in the tournament at the age of 38.

Torres was the one who was present in the opening and closing of this 15-year-old chapter in which Puerto Rico stood their ground as a continental basketball elite and a team to be respected in any world stage. Puerto Rico defeated the locals by a single point, 87-86, with 30 points by Mincy, and raised the championship trophy of 1995. Its last trophy.

Mincy retired from the national team in 2001, and Ortiz said farewell to the continental tournaments in 2003 at the age of forty, and with a performance for the ages: 21 points, ten rebounds, ten assists, and seven blocks against Canada, in a win that qualified Puerto Rico to the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens.

From 1980 to 1995, fifteen years that turned Puerto Rican basketball into a religion. A well-documented transition throughout the achievements of two AmeriCup generations built by athletic masterminds that knew how to give priority to their team – and not their personal results.

FIBA